What Conspiratorial Thinking Conceals

By Frank Miroslav

It has become passe to note that the last decade has seen a rise in conspiratorial thinking. The rise of the internet and the subsequent democratization of outlet choice and technology to produce media has accelerated the general trend of distrust in established media and government that began in the 1960s/70s. With the revelation of genuine conspiracies such as the Epstein scandal, a far more open public sphere and the fact that now the public can easily compare notes with each other, the decline in institutional trust has become a seemingly permanent fixture of the political landscape.

Of course information technology being a trigger for social disruption is nothing new. Every new communication technology results in social shifts – from the printing press kicking off wars of religion and enabling a commercial society at scale, to the radio being a vector for Nazi propaganda, to television promoting a degree of unprecedented cultural conformity. When it comes to affecting society, the internet is novel in how it upends things, but the actual upheaval is totally predictable.

Those commenting on conspiratorial thinking tend to highlight the ways in which it acts as a replacement for ideology or religion, a theory or methodology that people can use to explain the ills of the world without engaging in the arduous process of trying to figure out the actual dynamics at play. But it’s also worth highlighting that the logic most conspiracies take have within them an implicit theory of change.

If a small group of elites can effectively orchestrate and manage the rest of society to bad ends, well then surely our society might one day be directed by a different group of elites towards good ends. For those who find the notion of bottom-up change through more organic means boring, unrealistic or intimidating, this perspective has an obvious appeal.

While the stereotypical adherent to this sort of thinking is a conservative – both the overwhelming hype around Trump as an individual who would single handedly save everything and the subsequent emergence and popularization (and globalization) of QAnon as a way to explain why Trump couldn’t deliver – this sort of reasoning can be found anywhere. Be it the faith that liberals had in Obama, the praises online tankies sing for Xi Jingping, the emphasis leftists have on the Mont Perlin Society as the trigger for a shift to neoliberalism or on the CIA as the reason various socialist projects failed. Some of these arguments are more fleshed out than others and may have actually happened, but the common assumption shared across all is that a small group of individuals can reliably direct society.

Now this is not to say that conspiracies do not happen! Our world is one rife with manipulation and deceit. From backroom deals, to the low-level scams of street hucksters and used-car salesmen, to the algorithmic news feeds that are optimized for selling ads, to shady moves by intelligence agencies and corporations, our world is one rife with intentional manipulation. This perspective is further augmented by the fact that some of these conspiracies are incredibly successful – see for example the recent revelation that a Swiss company that sold encryption machines had put in backdoors for their true owners (the CIA).

However it’s worth noting that most conspiracies fail. The speeches of politicians fail to inspire and people just vote their party line. The history of intelligence agencies like the CIA is one of mistakes and fuckups. Leftists infiltrate your industrialist-funded neoliberal think-tank and start teaching libertarian socialism to the children of elites (see chapter 5 of Markets in the Name of Socialism). Elites give millions of dollars to things like Project Veritas, which largely gets spent to boost the careers of obvious grifters.

I think a major reason why this gets overlooked is because there’s a variant of survivorship bias at play. Successful conspiracies are sexy and intriguing and therefore get attention, whereas failed conspiracies look stupid and are ignored by people looking for drama and downplayed by conspirators who want to save face. It’s also worth noting that there’s good reason for conspirators to obfuscate information regardless of what happens to either hide their advantage or their weakness.

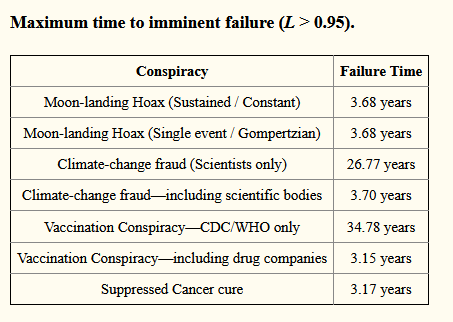

When seriously considered, the success rate of conspiracies suggests that the notion of a noble counter-elite taking power and righting the wrongs of the world is unlikely to work in any meaningful way. This isn’t to say that such a hypothetical elite will be entirely negative – that most things fail means that some things will occasionally work. The reason elite influence campaigns work is because they can effectively take a “portfolio approach” to affecting change that prioritizes a diverse set of approaches because they can afford. There is no grand master plan (at least no successful one), but a slow drip of change that occurs over time, punctuated by the occasional brilliant success. When you actually take the time to consider how many people would have to act in concert for major conspiracies to be successful, many would be undone within only a few years because the number of people required to go public and expose what’s going on is tiny compared to the number who work on it.

For those who have lived with the hope that they just needed to get the right people in charge, internalizing these insights is legitimately disheartening. But it’s also worth considering how this theory of change is actually pretty close to the common-sense assumption of how to make change in liberal democracies.

For a variety of reasons one of the implicit assumptions most people have about politics is that the primary way to affect the world is by getting a lot of people to perform simple tasks that elevate a small set of elites into a position where they can affect things according to some rational plan of how things ought to be.

Once upon a time this was a workable description of the world. When things were decided at the ballot box or the battlefield, what the average soldier or voter thought was irrelevant. Indeed critical thinking may have been a liability if it hurt the overall cohesion of the collective. Of course – which is why you can find examples of more decentralized forms of organizing beating rationalized hierarchies in the early modern period – but it worked well-enough that this model of the world was workable.

Our world has changed since then.

The advance of technology enables small collectives, loose networks and even individuals to perform actions that once required massive bureaucracies. This does not mean that all individuals are equally empowered or that there aren’t new emerging forms of domination to be concerned about, but the changes are significant and worth considering.

A major consequence of this is a distributed version of the portfolio approach to social change is increasingly possible. By giving people the tools and knowledge to act for themselves, a plurality of approaches become ever more possible.

Now to be fair, many are ignorant of these shifts because they are disempowered, disinterested and/or overwhelmed. That’s understandable. It’s those who both believe they are politically savvy yet remain convinced of an outdated way of doing things who are engaging in sloppy thinking who are behaving irrationally.

Follow political chatter by anyone on social media and you’ll see examples of this everywhere. Conservatives or reactionaries assuming that the left operates on a strict command and control structure managed by a shadowy cabal.

Or the insistence by some liberals that Trump was primarily the result of Russian election interference [1], and not systemic isolation and deprivation (worth noting this deprivation was not economic). That conservatives can be brought back to reality, despite the plummeting trust in media institutions and lack of incentives to think critically outside of platitudes about democratic principles.

Or even many socialists who, upon seeing average people all across the world utilize information technology to fight in a self-consciously fluid, decentralized manner, assume that this is a prelude to those people being herded into traditional leftist organizations to build traditional unions and vote for socialist politicians. That despite all the change in both labor relations and our understanding of organization since the heyday of the workers movement, that our best option is still some old formula.

In all cases what we have are people who are spinning their wheels, trying to avoid facing the fact that they have outdated models of the world that fail to grasp essential dynamics. This is not to say they have no predictive value – some leftist organizations have absolutely been funded by shadow figures trying to influence broader society,[2] some liberals may rescue conservatives currently ensnared by conspiracy and some leftist political parties that emerge in the coming years may even see success electorally. But the approaches are suboptimal, based on flawed models and will see decreasing returns as industrial-era institutions are less and less fit.

It’s those who can throw off tired old narratives and try to find solid ground in the midst of the upheaval, to try and reach for deeper dynamics that actually capture something solid in the shifting landscape that will have the potential for an outsized degree of agency and influence in the years to come.

To surmise, conspiratorial thinking is the expression of the hope for a better world that embraces shortcuts to avoid the task of trying to accurately model and understand the state of affairs. It is a cheap balm for anxious minds overwhelmed by a complex world, a secular replacement for the relief that religion provided with the knowledge that everything that happened was part of some cosmic plan. Going beyond this mindset while trying to be an efficacious actor means grappling with the anxiety that comes with taking on the responsibility of actually trying to figure out what’s going on. This process is uncomfortable and demanding but the alternative is uncomfortable, frustrating, demoralizing, and in the face of existential risks, potentially catastrophic. Only by grasping at more fundamental rooted dynamics do we have any hope of reliably affecting the world in any meaningful way.

This isn’t to say that there was no subterfuge done by Russia (or any other state), but rather that its impact was low enough such that it could have been worked around and that it should been expected because of course states will take a chance to mess with their geopolitical rival if the cost is low enough. But for many liberals, “Russiagate” is, like Qanoners, a way to provide a simple explanation for the state of the world that evades the collective responsibility for harder problems like addressing entrenched rent seeking or building a media ecosystem that can handle the complexities of the information age.

See for example the influential literary magazine Encounter, that was funded by the CIA (although this was revealed about a decade after the magazine started, proving my point about the difficulty of maintaining a conspiracy).