The Breakdown of Westphalia

Note: This short essay is part of the Series by emmi and Frank entitled, “Adapting to Transcend Networked Conflict: How complexity is our biggest asset” which can be found in full here.

The 30 Years War in Central Europe ended in 1648. It was a catastrophic event that resulted in at least 4.5 million deaths. The war resulted in the peace treaty of Westphalia between the various German states involved. The solution to the problems that set off the initial war was the concept of sovereign nation-states, political entities that have complete control over everything in their borders.

This ideal became more and more real in the 19th century when developments in productive and administrative technologies allowed it to manifest, at least in Europe. While we’ve never seen a state sufficient to manage everything within its borders, governments around the world were close enough to the ideal such that it worked pretty well as a descriptive lens of geopolitics in areas where the state had become strong enough.

But this model of the world has been breaking down since its peak in the second half of the 20th century. This breakdown is not an immediate break, but is rather one of nonlinear decay on the edges. Instead of a classical revolution wherein the masses storm the halls of power, we will have an increasingly contested world where nation states across the world face competition in various domains that they previously had relative dominance over.

Should the trends we describe continue, the median world in the next 2-3 decades will be one wherein territorial claims of nation states will be far more nebulous and they will have a diversity of competitors for providing services like dispute resolution, territorial defense, welfare, etc to people.[1]

Finally, before we begin, we should stress that our analysis here is not normative. While we obviously think that there are possibilities for increased freedom to be found in the disruption of the nation state, there are also serious risks. Many reactionaries openly hunger for the breakdown of the global order precisely because it will let them create insular communities free from outside influence. Or perhaps we’ll see the emergence of a multipolar world with China and the US as new superpowers, which might narrow the Overton window to a point not seen since the Cold War. Absolute prediction is impossible, but we can highlight trends that we believe will be influential in the future.

With all those caveats out of the way, let us begin.

The first way we are seeing states erode is through a decay of their defining feature, namely having a monopoly on force in a given area. While nation states as entities are still the undisputed when it comes to raw coercive capacity, they are now facing competition from other entities that complicate simplistic geopolitical models that assume the only relevant actors are other nation states.

This is an erosion of hard power, the ability of a state to maintain a monopoly on violence within a geographic region and to project that force outside said region.

Hard power decay comes in a variety of ways, the most obvious of which is the decline of state on state conflict. A major reason why this happened is the emergence of nuclear weapons, which upset the common sense that had reigned for over a century. The military historian Martin van Crede notes:

[N]uclear arsenal[s] tend to act as an inhibiting factor on military operations. As time went on, fear of escalation no longer allowed these countries to fight each other directly, seriously, or on any scale. As time was to show, the process took hold even where one or more of the nuclear states in question was headed by absolute dictators, as both the USSR and China were at various times; even when the balance of nuclear forces was completely lopsided, as when the United States possessed a ten-to-one advantage in delivery vehicles over the USSR during the Cuban Missile Crisis …. In fact, a strong case could be made that, wherever nuclear weapons appeared or where their presence was even strongly suspected, major interstate warfare on any scale is in the process of slowly abolishing itself. What is more, any state of any importance is now by definition capable of producing nuclear weapons. Hence, such warfare can be waged only either between or against third- and fourth-rate countries.[1]

The result was a complete upheaval of inherited assumptions about strategy. Crede continues:

[D]uring World War II four of seven … major belligerents had their capitals occupied. Two more (London and Moscow) were heavily bombed, and only one (Washington, DC) escaped either misfortune. Since then, however, no first- or second-rate power has seen large-scale military operations waged on its territory.…

The significance of this change was that strategy, which from Napoleon to World War II often used to measure its advances and retreats in hundreds of miles, now operates on a much smaller scale. For example, no post-1945 army has so much as tried to repeat the 600-mile German advance from the River Bug to Moscow, let alone the 1,300-mile Soviet march from Stalingrad to Berlin. Since then, the distances covered by armies were much shorter. In no case did they exceed 300 miles (Korea in 1950); usually, though, they did not penetrate deeper than 150 or so. In 1973 Syria and Egypt faced an unacknowledged nuclear threat on the part of Israel. Hence, as some of their leaders subsequently admitted, they limited themselves to advancing ten and five miles respectively into occupied territory.”[3]

Recent conflicts between nation states have followed this trend. The Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan was fought over territory only spanning a couple kilometers. Likewise, the only casualties in the recent Chinese-Indian standoff in the Kashmir region came from a skirmish that involved rocks, fists and iron bars at night in the Himalayas. The Syrian Civil War, while not a conflict between nation states, did see significant territorial shifts (mostly resulting from ISIS taking serious territory from the Syrian state) and resulted in a destabilizing refugee crisis, but the number of soldiers involved was similar to other civil conflicts.

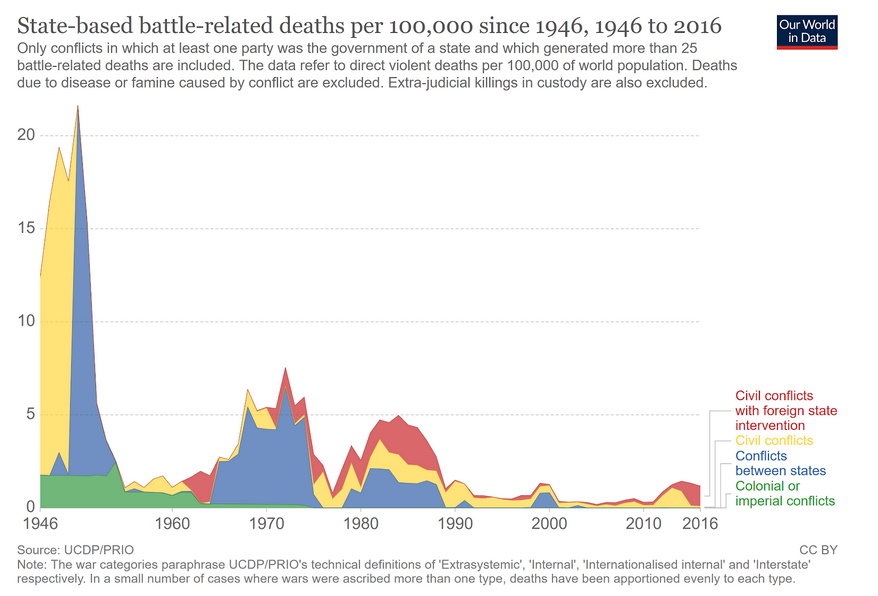

The decline of state-on-state conflict

Now of course these conflicts are still awful for those involved and we don’t want to downplay them or any other conflict in the world today. Nor do we want to ignore the possibilities of say, unrestricted cyberwarfare or the apocalyptic possibility of hot war between nuclear powers.[4] Nevertheless there does seem to be a trend away from outright conflict between established nation states.

When it comes to approaches to conflict, we’ve seen the emergence of more asymmetric approaches that leverage the rigidity of states. The coercive capacity of states still overwhelms the coercive capacity of non-state entities, but if they cannot deploy that capacity effectively, then they can be undermined by weaker actors. Hence the most common form of contemporary conflict tends to be between either non-state actors and states or non-state actors fighting each other. Terrorism, criminal gangs, militias, paramilitaries and guerrillas have become the main actors in conflict today, a reversal from the mass armies that were the mainstay since the French revolution.

This is reflected in the statistics. A study of asymmetric wars by Ivan Arreguín-Toft reveals that in the period from 1800-1849, the strongest actor came out on top in conflict 88% of the time.[5] Fast-forward to the period between the 1950s and the 1990s and the weaker actor wins slightly over half of all conflicts. Arreguín-Toft’s explanation for why this happened was that powerful states orientated themselves to fighting both the high tech mechanized war and nuclear combat, while weaker states moved in the direction of guerrilla warfare. Moreover the civilian population of the stronger side had less willingness to endure the costs of the drawn out warfare that guerrilla warfare involved. The fact that the struggle for the weaker side had existential implications gave them the motivation necessary to endure the significant casualties that such warfare involved.

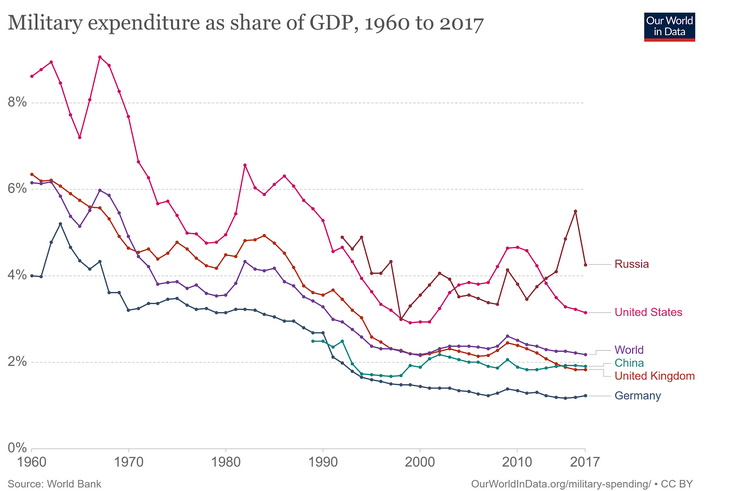

General decline of military expenditure as share of GDP

The decline in military spending after the Cold War, combined with shifts in the geopolitical landscape and the unreliability of nation states resulted in a rise in private military companies. While the nature of the industry makes it difficult to find solid numbers on just how big a role private military companies play, P.W. Singer estimates that it made roughly $100 billion a year in 2004.[6] To put that number in perspective, only the United States had a bigger military budget that year.

Private military companies mark something of a return to pre-modern norms. It was only with the Napoleonic wars that we saw a turn towards mass standing armies and with them the rise of the nation state capable of not just administering and provisioning armies out in the field, but also policing citizenry to extort taxes and enforce conscription. This era is increasingly at an end. The core motivator that originally prompted the rise of centralized administrative entities was the sort of mass warfare that ended with the emergence of nuclear weapons.[7] Some other concern may arise in the future that demands similar levels of mobilization, but at this moment in time there is no such danger on the horizon for the vast majority of states.

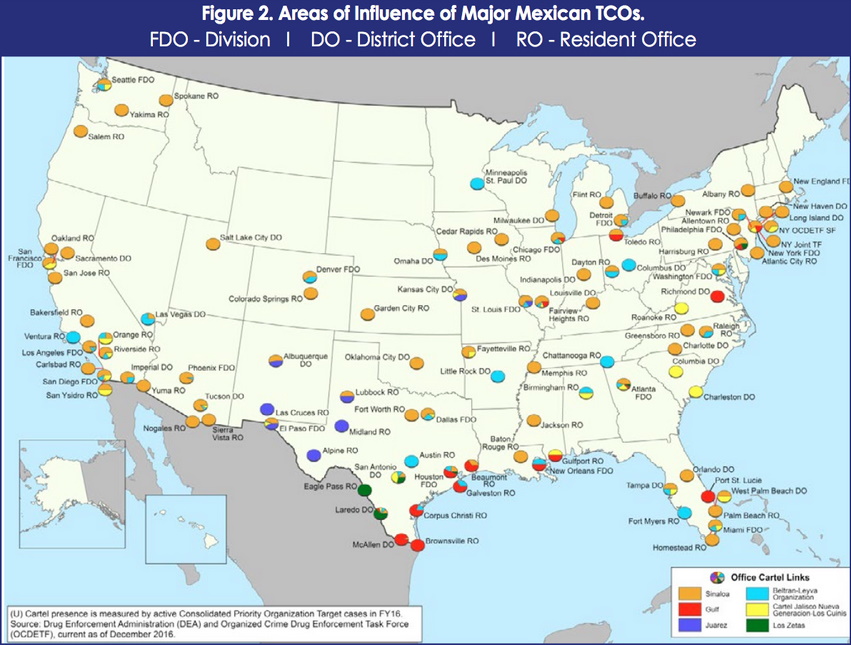

This rise in capitalist private armies is mirrored in the rise of multinational non-state actors like terrorists or gangs. The rise of multinational drug cartels that are based in Mexico are an easy example because of the sheer amount of resources that both the United States and Mexico spends trying to defeat them.

Drug Enforcement Administration map of the presence that various nacro cartels have in US cities

Attempts to end the drug trade by shutting down the border have been largely ineffectual. The inelastic demand for hard drugs in the United States gives cartels enormous incentive to try and get across the border. Hence cartels have invested in sophisticated technologies, like tunnels with electric rail lines across the border, custom “narco drones” to ship products and countermeasures that allow them to jam, hack and spoof drones used by the DHS on the border. This is all possible because drug smuggling is a billion dollar industry.

While cartels and private military will never be able to rival the military capacity of the United States or even Mexico in raw firepower, they don’t need to. Our point is that these trends are eroding the notion of geographic monopolies on power, making borders and territory more fluid. These emergent groups undermine the notion of a formal state with control over a particular territory by complicating its ability to direct behavior within its territory.

The disruption of control within an area might not sound like much. It is, after all, a far cry from the sort of territorial conquest that defined classic industrial era state-on-state conflict. But it’s worth remembering that small disruptions to processes can compound over time. A good example of how this might work can be found in the military theorist John Robb’s book Brave New War. He notes that terrorist attacks do not need to destroy a particular target to be successful, they merely need to impose a “terrorism tax” through direct costs that come through direct damage to the city and indirect costs in the form of the security required to defend against such attacks. His summation of the dynamics follows:

“[A]s a rule of thumb, a terrorism tax of 10 percent would be sufficient to push a city to significantly lower equilibriums—it would cause workers and firms to leave the city for other locations until the city ceased to be a target or became less expensive to defend.” [8]

Hence small, dedicated groups of people can increasingly impact much larger groups of people through the exploitation of weak spots. Such assumptions for economic concentration apply not just for cities but any economic activity that relies on significant investments. (Disruptions like unforeseen extreme weather events brought about by climate change or geopolitical upheaval can have a similar impact, even if they aren’t intentional).

Of course such terroristic acts also have a both psychological and moral dimension to them, which brings us to the other way the nation state is eroding, namely in the domain of soft power.

Soft power simply refers to the legitimacy of the institution in the eyes of people it rules over. And while that might not sound like much, it is vital for the system to work. The point is not that a diminishment of soft power will automatically lead to revolts and revolution, but that it reduces the overall efficiency of the system, which in turn makes it less capable of imposing edicts.

There are two general ways that soft power erodes. The first is through heightened disillusionment and distrust with the state. The second is through the emergence of genuine competitors to the state that provide services such that the state is no longer seen as the default actor for providing public goods.

The most obvious place to look for soft power erosion is with how the popularization of the internet impacted how people perceive the state across the world. As Martin Gurri writes:

“The grand hierarchies of the industrial age feel themselves to be in decline, and I’m disposed to agree. They evolved to operate on a more docile social structure — one in which far less information circulated far more slowly among far fewer persons. Today a networked public runs wild among the old institutions, and bleeds them of the power to command attention and define the intellectual and political agenda.

Every expert is surrounded by a horde of amateurs eager to pounce on every mistake and mock every unsuccessful prediction or policy. Every CRU has its hacker, every Mubarak his Wael Ghonim, every Barack Obama his Tea Party. Nothing is secret and nothing is sacred, so the hierarchies some time ago lost their heroic ambitions and now they have lost their nerve. They doubt their own authority, and they have good reason to do so.” [9]

This decline in trust has coincided with the emergence of alternative institutions and mechanisms for delivering the various services that states are supposed to provide. For example, the widespread adoption of cryptocurrencies in countries like Nigeria or Argentina to avoid financial instability shows that the technology has gone from being a speculative asset and another way for the rich to dodge taxation to being something that actually has some utility.

We also see this in the domain of welfare. From the existence of non-state entities like gangs and militias who provide services for their community. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic in parts of Mexico and Brazil it was local gangs that imposed curfews on citizens because the state was so weak. Or how Hezbollah provides healthcare and infrastructure to people in Lebanon, while also openly assassinating journalists that disagree with them (as seen with Lokman Slim). And of course in the United States, mutual aid organization was essential in covering the holes in both the COVID-19 outbreak and the recent collapse of the Texas energy grid. Ambitious projects like Four Thieves Vinegar and Open Insulin look to replace parts of the bloated medical system with significantly more efficient alternatives.

Finally there’s examples of routing around formal decision making processes. Groups like the C40 network of cities (which, at time of writing, contains 97 cities which make up 1/4th of the global economy) are an example of this in practice. Frustrated with the lack of national action against the threat of climate change, this group of cities is looking to accelerate the transition towards a green economy through lateral coordination and communication that bypasses traditional channels of state-to-state communication.

Such autonomous action may lead to some decentralization of delegation simply because the decentralized alternatives will not relieve pressure on states, but will also empower those who rely on it to fight for their autonomy. Obviously the respectability and power of the institution matters here — superstar cities are far more likely to have more formal autonomy by the end of decade compared to, say, gangs — but the overall trend of increased capacity of entities contained within a formal nation state means a more complicated landscape that hurts of states to act unilaterally. This dynamic could emerge in other domains, such as with common resource management schemes to manage infrastructure on the moon.

Now all these examples are, to varying degrees, parasitic on the states that they reside in. None of them will be able to replace the state its entirety immediately. But again, just like the prior examples of hard power erosion, what’s going on here is not the immediate overthrow of the existing system, but rather the emergence of an complex environment where the ability for states to enact sweeping action becomes harder and harder. The simple model of a sovereign entity that rules over a given territory and resolves all disputes/provides welfare is less and less descriptive of our world and how it works.

If we are correct about this dynamic, there will be many consequences, some good and some bad. Assumptions around security and welfare will require significant change. Models of risk management that assume sweeping edicts from states to prevent disaster will be increasingly seen as pure fantasy and will have to be rethought. Political approaches to change that rely on seizing positions through electoral means will find themselves empty-handed as they find themselves in control of an apparatus unable to bring about their desired ends (this applies to socialists, conservatives). Moreover this dynamic of increasing complexification will not unfold in a uniform, linear fashion across the world. Some areas may find themselves able to hold on to the industrial model (for whatever reason) for longer than others, while others will slip towards this new model much faster. We may see successful retrenchments of state power that leverage existing or emerging technologies in various regions. Despite all this we believe that, barring outright collapse, the most likely future is one where unitary state sovereignty over a particular region is far more complicated and there is significantly more choice for the average person when it comes to the public goods that states are supposed to provide.

But what we feel to be most interesting about this trajectory are the potentials around productive technology. To explain why, lets take a detour back to the beginning of the industrial revolution.

One of the most frustrating things about the contemporary moment is that partisans of all stripes assume that the outcome of the industrial revolution was an inevitability. We may one day create a world that transcends the violence that lead up to our present moment, but they were a necessary part of technological progress and we can only hope to minimize the damage.

But there’s good reason to doubt such a simple narrative. While we may never know the true space of possibilities that could have emerged after the industrial revolution got started in Britain, we should be highly skeptical of deterministic accounts.

To begin with, we should consider the technological form that predominated in Europe prior to the industrial revolution. In his classic text, Technics and Civilization, Lewis Mumford notes that prior to the industrial revolution there was for several centuries the emergence of what he called the “eotechnic” phase wherein economic activity was primarily done using small-scale machinery. Renewable energy in the form of wind or water power was employed as the prime mover for mechanical productions. As he writes:

“Grinding grain and pumping water were not the only operations for which the water‐mill was used: it furnished power for pulping rags for paper (Ravens‐burg: 1290) : it ran the hammering and cutting machines of an ironworks (near Dobrilugk, Lausitz, 1320) : it sawed wood (Augsburg: 1322) : it beat hides in the tannery, it furnished power for spinning silk, it was used in fulling‐mills to work up the felts, and it turned the grinding machines of the armorers. The wire‐pulling machine invented by Rudolph of Nürnberg in 1400 was worked by water‐power. In the mining and metal working operations Dr. Georg Bauer described the great convenience of water‐power for pumping purposes in the mine, and suggested that if it could be utilized conveniently, it should be used instead of horses or man‐power to turn the underground machinery. As early as the fifteenth century, water‐mills were used for crushing ore. The importance of water‐power in relation to the iron industries cannot be over‐estimated: for by utilizing this power it was possible to make more powerful bellows, attain higher heats, use larger furnaces, and therefore increase the production of iron.The extent of all these operations, compared with those undertaken today in Essen or Gary, was naturally small: but so was the society. The diffusion of power was an aid to the diffusion of population: as long as industrial power was represented directly by the utilization of energy, rather than by financial investment, the balance between the various regions of Europe and between town and country within a region was pretty evenly maintained. It was only with the swift concentration of financial and political power in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that the excessive growth of Antwerp, London, Amsterdam, Paris, Rome, Lyons, Naples, took place.” [10]

The dispersed nature of the eotechnic made centralized control difficult and weakened the coercive power of the state. But this mode of organization was replaced by what Mumford called the paleotechnic phase. The paleotechnic model was considerably more productive, but also demanded regimentation and centralization. This was because of the technical dynamics of how coal worked. As Mumford put it:

“[T]he steam engine tended toward monopoly and concentration….Twenty‐four hour operations, which characterized the mine and the blast fur‐nace, now came into other industries which had heretofore respected the limita‐tions of day and night. Moved by a desire to earn every possible sum on their investments, the textile manufacturers lengthened the working day…. The steam engine was pacemaker. Since the steam engine requires constant care on the part of the stoker and engineer, steam power was more efficient in large units than in small ones: instead of a score of small units, working when required, one large engine was kept in constant motion. Thus steam power fostered the tendency toward large industrial plants already present in the subdivision of the manufacturing process. Great size, forced by the nature of the steam engine, became in turn a symbol of efficiency. The industrial leaders not only accepted concentration and magnitude as a fact of operation, conditioned by the steam engine: they came to believe in it by itself, as a mark of progress. With the big steam engine, the big factory, the big bonanza farm, the big blast furnace, efficiency was supposed to exist in direct ratio to size. Bigger was anciency was supposed to exist in direct ratio to size. Bigger was another way of saying better. [Gigantism] was … abetted by the difficulties of economic power production with small steam engines: so the engineers tended to crowd as many productive units as possible on the same shaft, or within the range of steam pressure through pipes limited enough to avoid excessive condensation losses. The driving of the individual machines in the plant from a single shaft made it necessary to spot the machines along the shafting, without close adjustment to the topographical needs of the work itself.” [11]

Similar trends were detailed in Andreas Malm’s book Fossil Capital. Until the 1840s, water power was cost competitive with coal and could be used as a prime mover. But coal won out in the end for two main reasons.

The first was that capitalists found it difficult to cooperate in the task of maintaining infrastructure that would allow them to reliably use water. The inconsistency of water power was an obvious drawback when it came to industrialization, but by 1824 it had a solution, namely a system of dams and reservoirs that utilized automatic sulices to ensure a far more reliable supply of water. But because a single reservoir could supply water that powered the factories down the river at uneven rates and times made determining the exact amount each should contribute to the system’s upkeep difficult. Moreover it was difficult to exclude those who did not pay from accessing the river. The inability to overcome these limitations resulted in a tragedy of the commons that made water power hard to access. Early English capitalists simply couldn’t come together to cooperate on a project that would have given them long term benefits in the form of a much cheaper source of energy. [12]

The other benefit that coal had over water was that it enabled control over workers. Water power forced production to be carried out to a particular place, whereas coal could be transported and burnt anywhere. This allowed it to be carried to the towns where capitalists had a buyers market when it came to labor. The cost of replacing labor in the disparate water mills scattered across the country was sufficiently high such that workers had more bargaining power. Moreover capitalists at these mills had to provide amenities to workers, which made riots more damaging. Finally there was the inadvertent impact of legislation – the Factory Act of 1833 which set limits on work hours. The result was more powerful steam engines built, which increased the productivity of mills such that the time could be made up. Water mills on the other hand did not have an immediate innovation to make up for the lost time. [13]

But the centralized tendency that technology headed in was by no means inevitable. Mumford contrasted the paleotechnic model with a potential “neotechnic” order. The neotechnic phase was defined by technologies that would reverse the incentives that resulted in concentration and monopoly. Key to this was the discovery of electricity and various inventions that allowed it (the dynamo, the alternator, the storage cell and the electric motor). Electricity, which could be generated from a multitude of sources and transmitted across great distances for very little. This combined enabled small-scale productive machinery that was flexible and efficient. As Mumford writes:

“The introduction of the electric motor worked a transformation within the plant itself. For the electric motor created flexibility in the design of the factory: not merely could individual units be placed where they were wanted, and not merely could they be designed for the particular work needed: but the direct drive, which increased the efficiency of the motor, also made it possible to alter the layout of the plant itself as needed. The installation of motors removed the belts which cut off light and lowered efficiency, and opened the way for the rear‐rangement of machines in functional units without regard for the shafts and aisles of the old‐fashioned factory: each unit could work at its own rate of speed, and start and stop to suit its own needs, without power losses through the opera‐tion of the plant as a whole…. [T]he efficiency of small units worked by electric motors utilizing current either from local turbines or from a central power plant has given small‐scale industry a new lease on life: on a purely technical basis it can, for the first time since the introduction of the steam engine, compete on even terms with the larger unit.” [14]

While neotechnic production might not be as efficient at producing a single commodity as the paleotechnic, it makes up for it by being both more flexible in terms of what it can produce and by. Hence the neotechnic model is superior in a more dynamic environment because it can more easily adjust to the change around it. Mumford writes:

“Even domestic production has become possible again through the use of electricity: for if the domestic grain grinder is less efficient, from a purely mechanical standpoint, than the huge flour mills of Minneapolis, it permits a nicer timing of production to need, so that it is no longer necessary to consume bolted white flours because whole wheat flours deteriorate more quickly and spoil if they are ground too long before they are sold and used. To be efficient, the small plant need not remain in continuous operation nor need it produce gigantic quantities of foodstuffs and goods for a distant market: it can respond to local demand and supply; it can operate on an irregular basis, since the overhead for permanent staff and equipment is proportionately smaller; it can take advantage of smaller wastes of time and energy in transportation, and by face to face contact it can cut out the inevitable red‐tape of even efficient large organizations.” [15]

The anarchist Peter Kropotkin noticed similar technical possibilities in his work Fields, Factories and Workshops. Contra Marxist assumptions about the inevitability of capital becoming concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, what instead was happening was the emergence of petty smallholders that could exist alongside large factories. As Kropotkin writes:

“Consequently, to affirm that the small industries are doomed to disappear, while we see new ones appear every day, is merely to repeat a hasty generalisation that was made in the earlier part of the nineteenth century by those who witnessed the absorption of hand-work by machinery work in the cotton industry — a generalisation which, as we saw already, and are going still better to see on the following pages, finds no confirmation from the study of industries, great and small, and is upset by the censuses of the factories and workshops.” [16]

Kropotkin credited electricity as what gave petty proprietors the ability to compete with large enterprises. As he writes:

“Far from showing a tendency to disappear, the small industries show, on the contrary, a tendency towards making a further development, since the municipal supply of electrical power — such as we have, for instance, in Manchester — permits the owner of a small factory to have a cheap supply of motive power, exactly in the proportion required at a given time, and to pay only for what is really consumed.” [17]

Unfortunately the neotechnic model has never really been adopted by any society at scale. While we have some examples of it in action, such as in the Emilia-Romagna region in Italy, the Toyota production in Japan that relies on Lean manufacturing principles and the hacker-entrepreneurs known as the shanzhai in China.

A major reason why is that the state tipped the balance in favor of the paleotechnic model for reasons of control and stability. One way they did this was the construction and maintenance of transportation networks that made the economies of scale for centralized factories actually have a place for all that output to go. Michael Piore and Charles Sabel’s The Second Industrial Divide details how dependent centralized mass production was on transportation networks. They note:

[I]f any single external factor was crucial to the corporation’s success, it was the railroads. … First, the railroads were critical to the mass produces because they aggregated a homogenous but geographically dispersed demand. … Second, it is arguable that the railroads’ policy of favoring their largest customers, through rebeats, assured the survival of sugar- and petroleum-refining trusts during their formative years. Although these trusts undoubtedly profited from the economies of scale permitted by combination and market stabilization, such increased efficiency would have not necessarily guaranteed the survival of the new organizations in the absence of favorable treatment from railroads. … [S]een in this light, the rise of the American corporation can be interpreted more as the result of complex alliances among Gilded Age robber barons than as a first solution to the problem of market stabilization faced by a mass-production economy.” [18]

Such railways relied upon significant state subsidies to come about. As they write:

“The railroad’s start-up costs were huge – securing right of way, preparing roadbeds, and laying track – and the return on investments were far from assured. It is unlikely that the railroads would have been built as quickly and extensively as they were but for the availability of massive government subsidies. These ranged from straightforward (if illegally obtained) concessions regarding right-of-way to revisions of tort and contract law.” [19]

Similar dynamics are seen in the contemporary highway system in places like America. These are largely funded by fuel taxes, but since most of the damage done to roads is through the operation of heavy vehicles it acts as a defacto subsidy. As Kevin Carson writes:

“Virtually 100 percent of roadbed damage to highways is caused by heavy trucks. After repeated liberalization of maximum weight restrictions, far beyond the heaviest conceivable weight the interstate roadbeds were originally designed to support, fuel taxes fail miserably at capturing from big-rig operators the cost of pavement damage caused by higher axle loads. And truckers have been successful at scrapping weight-distance user charges in all but a few western states, where the push for repeal continues. So only about half the revenue of the highway trust fund comes from fees or fuel taxes on the trucking industry, and the rest is externalized on private automobiles.” [20]

The result was that the neotechnic order could never flourish. Its mechanisms were repurposed for the same old top-down centralized management style. Mumford lamets:

The present order is, socially and technically, third‐rate. It has only a fraction of the efficiency that the neotechnic civilization as a whole may pos‐sess, provided it finally produces its own institutional forms and controls and directions and patterns. At present, instead of finding these forms, we have applied our skill and invention in such a manner as to give a fresh lease of life to many of the obsolete capitalist and militarist institutions of the older period. Paleotechnic purposes with neotechnic means: that is the most obvious characteristic of the present order.[21]

A major reason why technology developed in such a fashion was how war was fought in the 19th and 20th centuries. The command and control style which was typified by the sort of mass mobilization, mass production and logistic trains, all of which had to be simple enough to be controlled by a centralized apparatus. This style of approach remained dominant in the Cold War, with the US and USSR structuring their respective militaries to fight both conventional wars and nuclear war.

Top-down command and control of armies required top-down control of the economy. A more decentralized economic model would be more efficient in a variety of ways than the centralized one. But decentralized would make the sort of total mobilization far harder to achieve. As James C. Scott writes:

“As a general rule, states of virtually all descriptions have always favored units of production from which it is easier to appropriate grain and taxes. For this reason, the state has nearly always been the implacable enemy of mobile peoples—Gypsies, pastoralists, itinerant traders, shifting cultivators, migrating laborers—as their activities are opaque and mobile, flying below the state’s radar. For much the same reason states have preferred agribusiness, collective farms, plantations, and state marketing boards over smallholder agriculture and petty trade. They have preferred large corporations, banks, and business conglomerates to smaller-scale trade and industry. The former are often less efficient than the latter, but the fiscal authorities can more easily monitor, regulate, and tax them.”[22]

Hence the production base of industrial warfare had to be centralized in relatively few hands so that it could be directed in times of need. Kropoktin noted that the process of decentralization that was occurring organically thanks to the introduction of electric power was avoided in the industries necessary for waging war. As he put it: “The absorption of the small workshops by bigger concerns is a fact which had struck the economists in the ‘forties of the last century … is continued still in many other trades, and is especially striking in a number of very big concerns dealing with metals and war supplies for the different States.”[23]

These trends around warfare were also noticed by John Boyd. His 1976 presentation, Patterns of Conflict, notes how modern warfare was never really able to shake the logic of command and control that had become entrenched in the 19th century. The emergence of mass production and transport networks had enabled a form of warfare that in his words “used technology as a crude club, generating frightful and deliberating casualties on both sides.” [24] Such a form of warfare was predicated on a “narrow fixed logistics network”. [25] The command and control approach “suppressed ambiguity, deception and mobility hence surprise of any operation.” [26]

Boyd defines such a model of warfare as “attrition warfare”, wherein success is measured by whichever side can bring the most firepower to bear and use it to inflict the most casualties. He contrasts this with two alternative modes of war, namely maneuver conflict and moral conflict which stress both the inherent uncertainty/ambiguity present to conflict and the sheer array of options available. Maneuver and moral conflicts are won not through inflicting sufficient casualties, but rather through disorientating the enemy and causing internal disruption such that they are no longer able to function.

In both cases, Boyd emphasizes the importance of a more decentralist, autonomous form of organization. The list of themes within moral conflict is especially telling. It involves:

- “No fixed recipes for organization, communications, tactics, leadership, etc.

- Wide freedom for subordinates to exercise imagination and initiative—yet harmonize within intent of superior commanders.

- Heavy reliance upon moral (human values) instead of material superiority as basis for cohesion and ultimate success.

- Commanders must create a bond and breadth of experience based upon trust—not mistrust—for cohesion.” [27]

Moral conflict is more demanding, both on commanders and subordinates, but once realized it allows for more flexible and dynamic forms of organization that can outmaneuver more rigid enemies. Boyd credits the early success of Napoleon to his ability to leverage moral conflict against his enemies. The self-motivated energy of French citizens who had joined the army to fight for the ideals of the French revolution allowed for far greater discretion and autonomy for the average soldier. Such armies could self-organize in a decentralized fashion and were also capable of traveling light and living off the countryside. The result was a significantly more mobile/fluid force that could outmaneuver opponents both strategically and tactically. It was this flexibility and dynamism that allowed Napoleon to win battles even when he was outnumbered. [28]

But such an approach only had purchase within a specific context. As war weariness set in and the intrinsic motivation dissipated, Napoleon had to restructure his army along largely centralized lines, restricting agency of subordinates such that they could be managed. After becoming emperor, Boyd notes that Napoleon:

- “[E]mphasized the conduct of war from the top down. He created and exploited strategic success to procure grand tactical and tactical success.[sic]

- To support his concept, he set up a highly centralized command and control system which, when coupled with essentially unvarying tactical recipes, resulted in strength smashing into strength by increasingly unimaginative, formalized, and predictable actions at lower and lower levels.” [29]

Beyond Napoleon, the only examples Boyd has of decentralist forms of organizing in Europe in the 19th century are the Spanish and Russian guerrillas who resisted French invasion. Outside of those exceptions, the century was marked by centralized command and control.

Hence, despite Boyd never making it explicit, there were implicit class dynamics to his analysis of conflict. Maneuver and moral conflict requires a degree of relational egalitarianism between superiors and subordinates that attrition conflict can dispense with. While a more decentralized army might be more effective at winning wars, but it comes at the cost of being harder to manage.

The parallels to economic dynamics described by Mumford should be obvious. Paleotechnic industry relies on the suppression of agency of all but a few so as to maintain power. Neotechnic industry on the other hand benefits from the empowerment of all. The technological approaches also reward particular forms of conflict. Paleotechnic industry can support the mass production necessary and logistics that attrition warfare demands, but struggles to manage with more complex domains that demand adaptation and innovation. Likewise, the neotechnic industry is fantastic at iterating through solutions to problems and adjusting to a dynamic environment, but the dispersed nature of production, combined with the autonomy it requires in the people who work it, make the sort of command and control required to fight attrition warfare near impossible.

While most people would probably prefer a neotechnic complex, transition towards it would be incredibly rocky. We’re not just talking about undermining the ability of the state to impose edicts on the general populace, but also the renegotiation if not abolition of many other relationships of domination throughout society. The exact form society would take after the fact is impossible to determine ahead of time, but it would be seriously disruptive to established institutions, norms and assumptions.

But had a neotechnic society managed to organically emerge and grow without being eradicated in the last two centuries, we’d be living in a vastly different world. The mere existence of a significantly different way of doing things and investment in alternative technologies that seek to empower.[30] While, because of path dependency reasons, we cannot predict what such a society would look like, the mere existence of a different trajectory than the command and control that marked both the capitalist west and the socialist east would result in a significantly different technological trajectory.

We mention all so that you can understand just how big a deal the emergence of decentralized flexible productive technologies that are competitive with the existing industrial system are. Technologies like 3d-printers, computer controlled cutters and rooftop solar go from being novelties to being increasingly economically competitive. Here is a preliminary survey (as of 2021) on the economics of small-scale productive technology:

- Petersen, et al (2017) showed that 3d-printing could produce certain plastic toys with 40-90% savings.[31]

- Petersen and Pearce (2017) showed that an average American household would see a payback time anywhere from 5 years to 6 months by owning a 3d-printer and printing common items that would normally be store bought.[32]

- Pearce (2020) showed that labs could see savings of 92% by 3d-printing certain pieces of scientific hardware.[33]

- A 2015 Guardian article on 3d-printing for humanitarian disaster relief claimed that there is potential for significant savings for small items like umbilical cord clamps because so much of the cost is transportation.

- The FarmBot, a small-scale farming robot, has a payback time anywhere from 4 years to 6 months.[34]

- The current payback time for owning solar panels is, as of 2021, 8 years.

- Anyone can 3d-print the base of guns for a couple dollars (although you’ll need to buy gun kit parts to finish).

While such a summary ignores things like differences in quality, skills barriers and local context, what it nevertheless shows is that we are increasingly moving to a world where access to the means of production will be considerably more democratized. Not every commodity can be reasonably localized with our current technological configuration, [35] but even a moderate shift in terms of decentralizing productive capacity will have significant consequences. We’re nowhere close to the utopian world of Star Trek replicators where every person can have the entire means of production on their desk, [36] but we don’t need that for a renegotiation of the global economy. Just like the prior examples of hard/soft power, what we have is not some overnight collapse, but rather an erosion of capacity in some domains.

What these technologies ultimately offer is what the philosopher Pete Wolfendale called a “class war economy”. This sort of low-overhead, flexible, illegible productive technology is not just perfect for supporting those engaging in overt politics, it also has the virtue of subtly undermining the capitalist order on various fronts by both offering various products cheaper.

Do Your Part, Buy a 3d-Printer and Join the Class War Economy Today!

We are never going to be able to out-hierarchy the control hierarchies that rule our world. But instead of fighting them head on, we can instead erode them by creating a structure that is more flexible and distributed. Over a long enough time frame, the distributed and flexible nature of the system means it will be both more resilient in the face of unexpected negative events and more capable of taking advantage of positive developments.[36] This means that it can eat away at the existing structure piece by piece.

Moreover many of these emerging technologies are open-source and hence, are partially non-rivalrous. The non-rival nature of the designs of such technologies is significant because it’s the non-rival nature of projects like Wikipedia or piracy that makes them the closest we’ve come to a functional mass communism.

Information is also easy to defend and transmit. The Tor internet network allows for a form of hosting that obscures the location of the host. VPNs and end-to-end encryption allow people to access and transmit information with security. In worst case scenarios like authoritarian clampdowns on internet access, techniques like steganography and sneakernets allow for information to cross borders.

All these developments frustrate attempts to control the process through measures like intellectual property law are fighting an uphill battle in this environment. When the majority of investment in the means of production are centralized, legible factories, the number of people you need to commit to actions like strikes or takeovers is high and the action is dangerous. But when the primary mechanism to capture profits is information, the critical mass required to make an impact is much lower.

This means that failure is less costly. While individual leakers face significant harm if they are caught and prosecuted, they can take some comfort in knowing that if the information is public, it cannot be put back into the bottle (as seen with Snowden or Manning). While this is obviously a terrible outcome for those punished, it’s a considerable strategic development over prior forms of struggle wherein defeat would mean not just the persecution of workers, but also revision to prior ownership arrangements.

Of course these technologies have dark sides. Privacy and peer-to-peer technologies can increase agency, while also be simultaneously harmful to society in some ways. While the current system of nation-states is responsible for systemic injustices and violence perpetuated at an unimaginable scale, this does not mean that there aren’t worse alternative arrangements. A fascist US is still worse in many ways than a liberal US, even if they’re both horrifyingly bad (don’t be fooled, they will both be imperialist).

While there have been successful stateless societies that have operated at scale, the notion that you can just undermine the state and that it will magically lead to utopia is hubris. As complexity theorists Yaneer Bar-Yam and Alexander S. Gard-Murray note in their paper Complexity and the Limits of Revolution, autocracy is statistically more likely to emerge from violent revolutions than democracy. The reason why is that democracy as a system is more complex than autocracy and thus requires more time to establish. The chaotic violence that marks post-revolutionary periods is extremely difficult to channel into liberatory experiments in social coordination. As Bay-Yam and Gard-Murray write:

“[W]hile states are sometimes portrayed as being formally planned, the successful implementation of such plans must depend on an incremental accumulation of complexity. Constitutions can be written quickly, but if they call for institutions which are more complex than existing ones, they will take significant time to implement. … [T]he process by which complexity increases does not necessarily occur at a steady rate. Complexity may increase more rapidly in one period than previously,as described by the theory of punctuated equilibrium in biological evolution. But even in cases of rapid increase, higher levels of complexity are still dependent on previously existing structures.” [38]

Once established, liberal democratic states tend to generally be more stable than more autocratic counterparts (in the modern context anyway). But they need to survive long enough before that becomes a reality and things like international conflict, war and colonialism play against that development. Similar dynamics will be at work with a transition to a stateless society. A functional mass stateless society will be considerably more complex than the liberal democracies we see today. As such, the amount of energy and time required to stabilize things will be higher.

But one virtue statelessness has over democracies in this regard is that a liberal democracy works through centralized formal institutions that are backed through a monopoly on violence. A stateless order on the other hand works through alternative mechanisms and as such does not always need to directly take those institutions head-on.

This speaks to a broader point, namely that forms of social organization are suited to particular environments. This is why lurking behind most social struggles over a particular concern are actually fights over the broader context that the struggle is merely a manifestation of. In his book Worshipping Power, Peter Gelderloos uses the term cratoforming – the process by which states shape the environment around them so as to make it more suited to their functioning. We need to undo this damage and create the sort of environment that states wilt in, namely one that is non-linear and dynamic.

At the same time, because overnight revolution will almost certainly result in a worse outcome, patience is necessary. Building a better world through this process of growing our capacity, there will be many detentes, appropriations, and compromises by states with our developments. As David Graeber put it “presumably any effective road to revolution will involve endless moments of cooptation, endless victorious campaigns, endless little insurrectionary moments or moments of flight and covert autonomy.”

[1] There of course is the potential for a reversal of these dynamics, perhaps driven by advanced technology that gives states. One such example are the near-ubiquitous centralized algorithmic surveillance systems of the sort being developed in countries like China that people fear/hope will be sufficient to overcome the trends we list. While this is certainly a concern, AI is decidedly not magic and hence is limited both by computational limits and by the incentive structure of authoritarian rulers. The short essay Seeing Like a Finite State Machine by Henry Farrell makes this argument in more detail.

[2] The Rise and Decline of the State, Martin van Crede, pg 344

[3] ibid pg 346-347

[4] As work like On the statistical properties and tail risk of violent conflicts by Pasquale Cirillo and Nassim Nicholas Taleb has shown, large scale conflict is sufficiently rare such that trying to predict the likelihood of it in the future is impossible.

[5] How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict, Ivan Arreguín-Toft

[6] Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry, P.W. Singer, pg 78

[7] Nuclear weapons programs are certainly costly, but their expenditure must be contrasted with the costs of maintaining a standing army. A good example of the cost of nuclear deterrence is a report by the British American Security Information Council which estimated that the Trident nuclear submarine defense system took up roughly 4.7% of the defense budget once procured.

[8] Brave New War, John Robb, Chapter 5

[9] Revolt of the Public, Martin Gurri, pg 249

[10] Technics and Civilization, Lewis Mumford, pg 114-115

[11] ibid, pg 224

[12] See chapter 6 of Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming by Andreas Malm

[13] See chapters 7 and 8 of ibid

[14] Technics and Civilization, pg 224-225

[15] ibid, pg 225

[16] Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow, Peter Kropotkin (intro by Kevin Carson, additional material by Colin Ward, supplemental material by Murray Bockchin), pg 109

[17] ibid

[18] The Second Industrial Divide, Michael Piore and Charles Sabel, pg 66

[19] ibid, pg 66-67

[20] The Distorting Effect of Transportation Subsidies, Kevin Carson, Foundation for Economic Education

[21] Technics and Civilization, pg 267

[22] Two Cheers for Anarchism, James C. Scott, pg 87

[23] Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow, pg 108

[24] Patterns of Conflict, John Boyd, pg 49

[25] ibid pg 48

[26] ibid

[27] ibid, pg 118

[28] ibid, pg 33

[29] ibid, pg 33

[30] Take for example David Noble’s Forces of Production: A Social History of Automation which details how American industry and the state pushed for the inferior numerical control automation system over the superior record playback system because it offered management more control over the workforce.

[31] Impact of DIY Home Manufacturing with 3D Printing on the Toy and Game Market, Emily E. Petersen et al, 2017

[32] Emergence of Home Manufacturing in the Developed World: Return on Investment for Open-Source 3-D Printers, Emily E. Petersen and Joshua Pearce, 2017

[33] Economic savings for scientific free and open source technology: A review, Joshua Pearce, 2020

[34] What is the FarmBot’s Return on Investment?

[35] Evaluating what can be reasonably decentralized and what can not when we have several centuries of innovation in a paleotechnic direction is difficult. Had the economy and research evolved differently the range of productive possibilities would be vastly different.

[36] We personally prefer the nanotech assemblers of Charlie Stross’ Singularity Sky that can fit in a pocket and resulted in a workers revolution against technophobic monarchists, but that book isn’t widely known so you get the reference that actually has pop-culture cache.

[37] For an overview of why organizational approaches that privilege decentralization and autonomy are superior at weathering negative uncertainty and benefiting from positive opportunities, see Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder.

[38] Complexity and the Limits of Revolution: What will happen to the Arab Spring?, Alexander S. Gard-Murray and Yaneer Bar-Yam, New England Complex Systems Institute, 2013